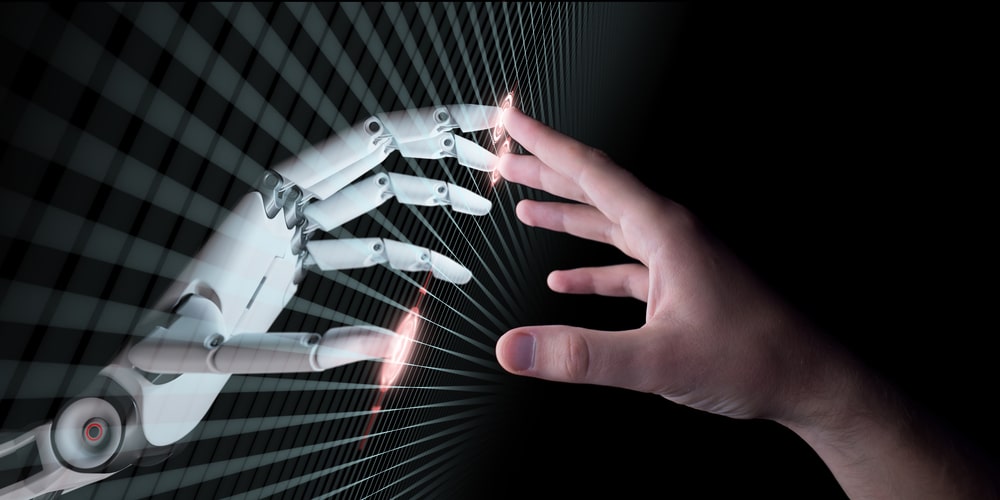

Scientists claim they have recovered material that originated outside our solar system for the first time in history.

Alien-hunting Harvard physicist Professor Avi Loeb said early analysis of metal fragments his team recovered from the Pacific Ocean in June suggest they came from interstellar space.

The 700 or so tiny metallic spheres analyzed contain alloys that do not match with any existing alloys in our solar system. The findings do not yet answer whether the spheres are artificial or natural in origin – which Loeb says is the next question his research aims to answer.

‘This is a historic discovery because it represents the first time that humans put their hand on materials from a large object that arrived to Earth from outside the solar system, Loeb wrote Tuesday on Medium.

The remnants came from a meteor-like object that crashed off the coast of Papua New Guinea in 2014, which Loeb is not ruling out could have been fragments of an alien craft.

He and a team spent two weeks in June trawling the seafloor in hopes of recovering evidence to hold up his theory. ‘The success of the expedition illustrates the value of taking risks in science despite all odds as an opportunity for discovering new knowledge,’ Loeb wrote on Medium.

He told DailyMail.com that future research would answer whether the fragments are natural or fashioned by otherworldly beings. ‘For now, we wanted to check whether the materials are from outside the solar system,’ Loeb said.

The 2014 meteor-like object, named IM1 crashed into the ocean in 2014, but it was only detected by Professor Loeb and Harvard researcher Amir Siraj in a retrospective analysis.

The Harvard scientists spent years working closely with the US military to pinpoint the impact zone near Papua New Guinea, combing through data to determine if and when the object fell from space.

This past June, Loeb and his team traveled to a site where the meteor IM1 was believed to have crashed nearly a decade ago.

IM1 withstood four times the pressure that would typically destroy an ordinary iron-metal meteor — as it hurtled through Earth’s atmosphere at 100,215 miles per hour.

Iron is already the principal ingredient in the toughest known kinds of natural meteors, so the Harvard duo has theorized that there must be something highly unusual about how the object came to be made.

And now a battery of tests on the recovered IM1 fragments, conducted at Berkeley, has proven that their chemical make-up is almost entirely iron: strong evidence in favor of the Harvard team’s most controversial theories about the object.

The Harvard team took care to ensure that the 50 spherical iron fragments dredged up from over a mile below the surface of the Pacific were, in fact, actual remnants from IM1.

First, Siraj narrowed down the final trajectory of IM1 as it burst into flames on its way toward the ocean, tracking its airbursts with US Department of Defense satellite data and local seismometers set up to monitor earthquakes and volcanic activity.

With high confidence that the final path for IM1 covered 6.2 square-miles (16 sq-km) of ocean near Manus Island, the team was then able to scrape the deep ocean floor with a large magnetic ‘sled’ — both along IM1’s path and several ‘control’ regions.