A polar bear in the Arctic, red foxes in Europe, penguins in Antarctica, and a wide range of other wild animals have been infected with the flu virus strain, which is currently spreading in dairy cattle in the U.S.

Up to 75% of new and emerging infectious diseases in people come from animals, and most of those can be traced back to wildlife. Monitoring wild animals for diseases can help scientists identify emerging health threats.

Government agencies in the U.S. and worldwide monitor wild birds for avian influenza, which spreads in bird populations without causing symptoms, and select animals for other pathogens.

But overall, there is “very little surveillance of wildlife for any diseases,” says Thomas Gillespie, a disease ecologist at Emory University.

An exception is animals that are commercially important, like deer that people pay to hunt. In 2020, outbreaks of avian flu in farmed poultry and wild birds started to increase worldwide.

Soon after, the virus started to kill mammals—seals from Chile to Russia to Maine, red foxes in Europe and the U.S., sea lions in Peru, and others.

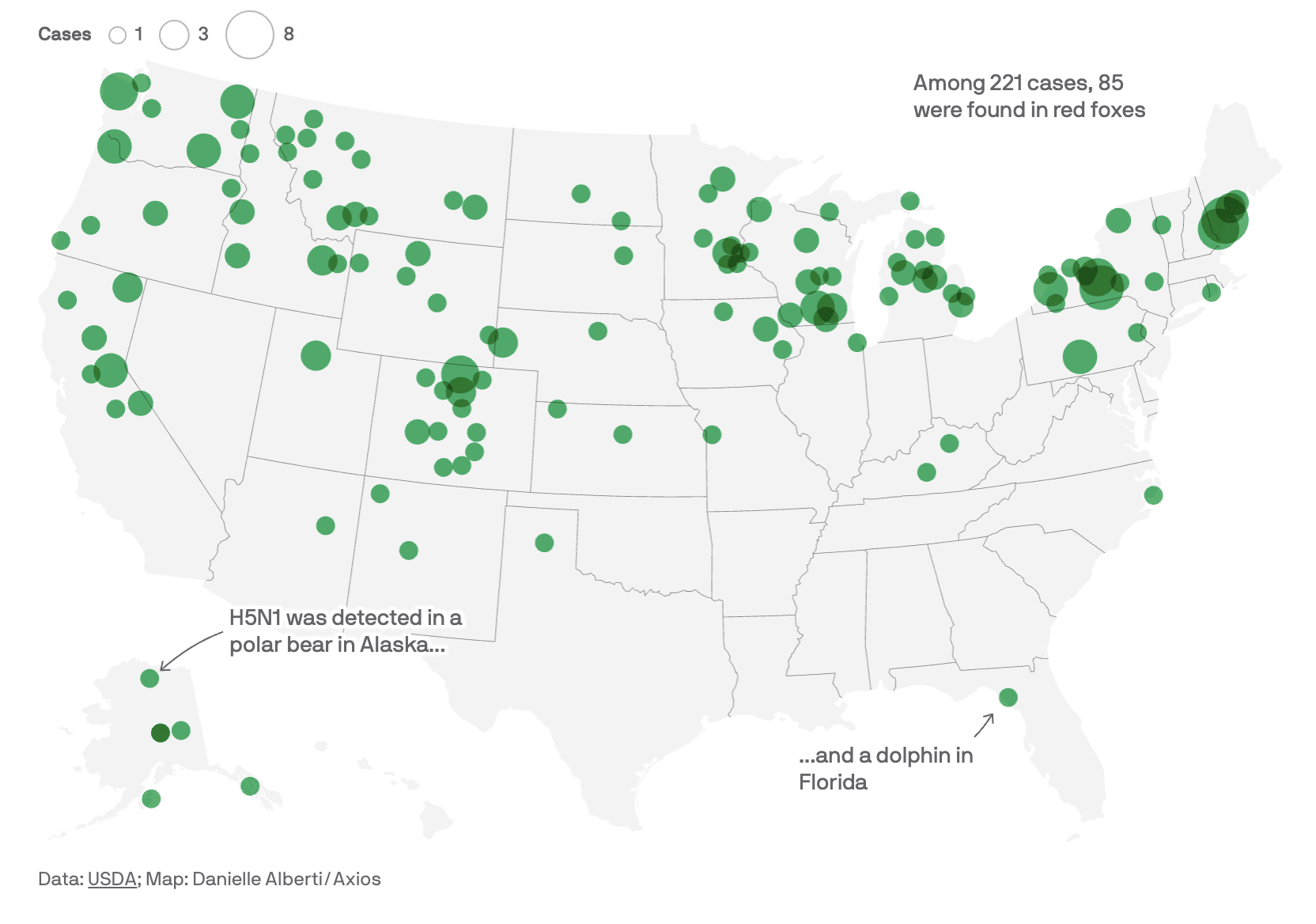

Bird flu has affected nearly 20 wild mammal species in the U.S. since 2022, including brown bears, skunks, mountain lions and a bottlenose dolphin in Florida.

Now cows are being infected. (They become ill but recover with treatment.) One mild human infection has been detected so far, in a person exposed to dairy cattle, but some researchers suspect not all cases in workers are being spotted.

A report published Friday suggests that may be “the first detected case of the H5N1 virus transmitting from a mammal to a person,” STAT’s Helen Branswell reported. The CDC has said the risk to the general public is low.