(OPINION) We know that Russian President Vladimir Putin is thinking about using nuclear weapons. He has twice warned the West not to intervene in Ukraine or face “consequences that you have never encountered in your history.”

Recently, Moscow again threatened “unpredictable consequences” if the U.S. continued sending advanced armaments to Ukraine. CIA Director William Burns has said that “none of us can take lightly” the prospect that Putin might resort to the use of tactical nuclear weapons.

While any use of a nuclear weapon is unthinkable to most of the world, under current Russian military doctrine — usually described in shorthand as “escalate to deescalate” — Putin could choose a nuclear “demonstration” as a warning to halt further American military aid to the Ukrainians. In other words, for the Russian leader, the detonation of a tactical nuclear weapon by Russia is entirely thinkable. And so the West needs to do some thinking, too.

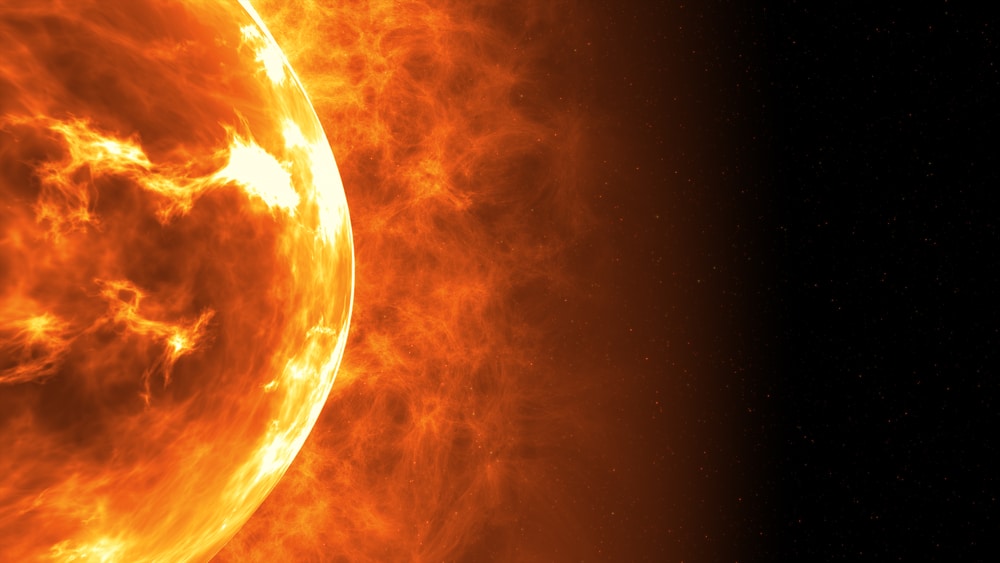

Tactical nuclear weapons are often called “battlefield” or “theater” weapons to distinguish them from much more powerful strategic nuclear weapons, but they are far more destructive than conventional weapons. During the Cold War, tactical nuclear weapons had yields ranging from tens or hundreds of tons of TNT to thousands of tons.

These weapons came in many forms: gravity bombs, short-range missile warheads, anti-aircraft missiles, air-to-air and air-to-ground missiles, anti-ship and anti-submarine torpedoes, and even demolition devices or mines. Reportedly, the smallest tactical weapon in the Russian nuclear arsenal has a yield of about one-third the size of Hiroshima or Nagasaki bombs, or equivalent to about 5,000 tons of TNT.

There are a few ways that such a tactical nuclear weapon could be used to fire the kind of “warning shot” envisioned in Russian military doctrine. These options come with increasing degrees of risk for the U.S., Ukraine and its allies, and for Russia. Here are three scenarios.

Scenario 1: Remote atmospheric test

Least provocative would be Putin’s resumption of above-ground nuclear testing — by detonating a low-yield nuclear warhead high above Novaya Zemlya, the old Soviet test site in the Arctic, for example. While both the actual damage on the ground and radioactive fallout would be negligible, the psychological effect could be enormous:

It would be the first nuclear explosion by a superpower since nuclear testing ended in 1992, and the first bomb detonated in the atmosphere by either the U.S. or Russia after such tests were outlawed by treaty in 1963. It would also be a potent reminder that Putin has tactical nuclear weapons in abundance — about 2,000 by last count — and is prepared to use them. CONTINUE