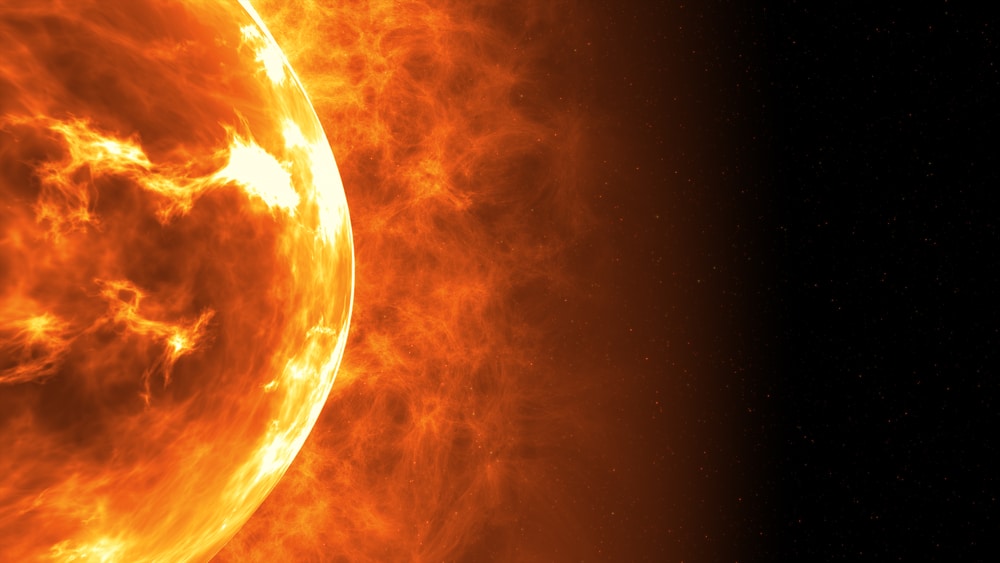

Our Sun has been crackling with activity lately, having already spewed over a dozen coronal mass ejections — large expulsions of plasma and magnetic fields from the Sun’s corona — this week.

Scientists have blamed a massive sunspot complex on the southern hemisphere of our star, which only seems to be growing in strength. But by the looks of it, the Sun is far from being done with its trouble-making ways.

Despite looking like harmless little dark spots that are cooler than their surrounding regions, sunspots are known to explode at the slightest provocation. Earlier this week, NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory spied four regions on the Sun that were very far from each other, exploding within minutes of one another.

At first glance, this may seem like a freak accident. Still, the three sunspots and a bigger magnetic filament (a large plasma and magnetic field structure extending outward from the Sun’s surface) that detonated are part of an event dubbed “sympathetic solar flares.”

As proved by a 2002 study, sunspots are sometimes linked to each other by nearly invisible magnetic loops in the solar corona. An instability in one of them can set off a chain reaction of explosions in all those other sunspots connected to it.

The sympathetic flare from Tuesday (April 23) was a complex quartet that covered much of the Sun’s Earth-facing side — making it “super-sympathetic”. The collective impacts of the blasts amounted to an M3 flare, which is a medium-sized solar flare or radiation burst capable of causing brief radio blackouts that affect Earth’s polar regions.

Guess what? Another sunspot has since joined this gang of delinquents. The five sunspots in the super group are AR3638, AR3643, AR3645, AR3647, and AR3650, and they are located just south of the solar equator.

The sunspots’ proximity fosters complex magnetic interactions, leading to frequent eruptions. The supergroup has produced a barrage of M-class flares throughout the week, with some near M-class intensity, as mentioned above.

Now, solar rotation will allow Earth to encounter the supergroup soon. This alignment could allow streams of charged particles ejected by solar flares to reach Earth’s magnetosphere via the Parker Spiral, a giant solar wind structure.

Experts predict a G1-class geomagnetic storm (minor on the severity scale) to occur today, possibly linked to earlier eruptions from the supergroup. This could potentially impact power grids and communication systems. However, a stronger storm is possible over the weekend (April 26-28) as the supergroup becomes fully Earth-facing.

This is a developing situation, and astronomers are closely monitoring the supergroup’s activity for any further impacts on Earth.