For the first time in five years, Gary Lynch’s company is so busy that he needed to leave his office to go help his employees in the field. His company sells steel bunkers and bomb shelters.

The general manager of the Texas-based Rising S Company had to help install a 1,600-square-foot model, which goes for a touch over $300,000. He told VICE News during his lunch break at the local Taco Bell that his company received over 700 inquiries recently, in a time frame where they typically would have received about 10.

“On Thursday morning, when we started seeing the nuclear threats, the phones started ringing immediately,” said Lynch. Some of the people who called were people who were already considering the need for a backyard bunker, and the Ukraine conflict is what finally pushed them over the edge.

A good chunk of the inquiries, Lynch said, were pretty frantic. Europeans are stocking up on iodine tablets (a Google Trends search shows near-vertical growth on that term in late February), and YouTube is suddenly full of “experts” giving advice on how to prepare for the end of the world.

Those in the “doomsday prepper” community say their community has been growing for years, with climate change, a global pandemic, and the general “end times” vibe of the last several years. But it has accelerated in the past weeks.

Nuclear anxieties triggered by the Russia-Ukraine war are only increasing. Growing up in Las Vegas in the 1980s, Glynn Walker always knew he could die in a nuclear attack. The 43-year-old engineer remembers “duck and cover” drills in elementary school, where you dive under your desk in the event of an air raid, and basement fallout shelters in churches and gymnasiums with radiation-warning signs on their doors.

“We had the nuclear test sites, Nellis Air Force Base, the Hoover Dam,” he said, referring to Nevada landmarks that likely were in the crosshairs of Soviet military strategists. “We knew we’d be a target,” he said. The prospect of nuclear war also permeated popular culture at the time, as it had done during the initial nuclear era of the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. Movies like “War Games,” “Red Dawn” and “The Day After” played on TV.

Pro-wrestling hero Hulk Hogan battled the villainous Russian Nikloai Volkoff right after Saturday morning cartoons. “99 Luftballoons,” a pop song about an accidentally triggered Armageddon, by the German New Wave band Nena, was a radio hit in the early 1980s.

“I can remember riding my bike through the desert as a kid and thinking one day this whole valley will be a radioactive hole,” Walker said. “I didn’t panic about it. It was just the way it was.” As the years passed, Walker stopped worrying about nuclear bombs as other threats emerged: terrorism, the war in Iraq, climate change.

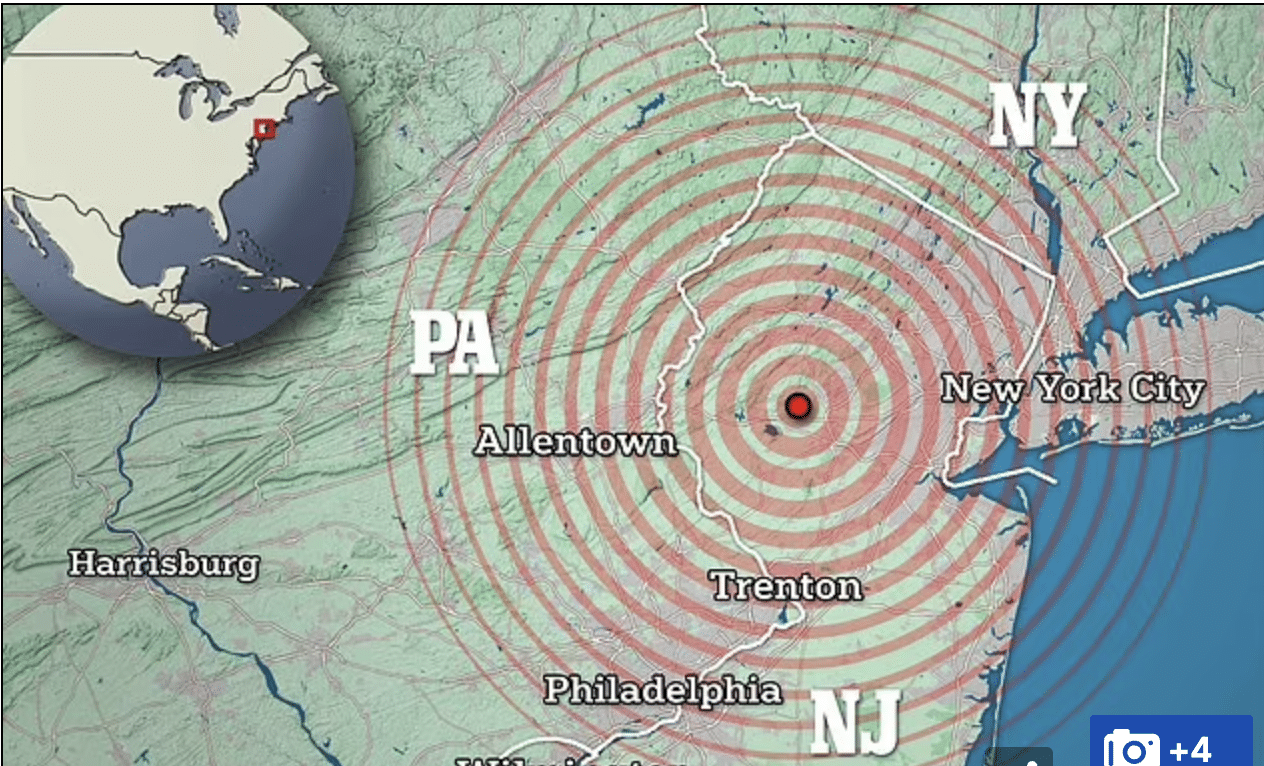

But the old anxieties came flooding back last week as Russian President Vladimir Putin launched a massive military invasion of Ukraine, while warning potential foes who intervened of “consequences greater than any you have ever faced in history,” and putting his nuclear forces on high alert.