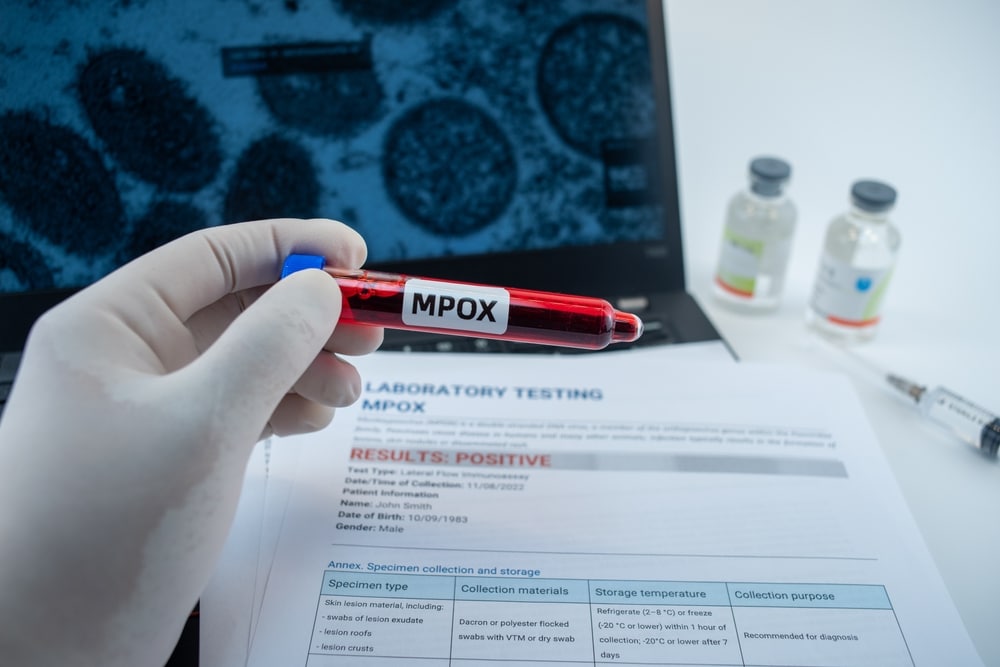

Officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said last week, however, there is a “substantial risk” of a resurgence this summer. This warning came days after the World Health Organization declared mpox to no longer be a global health emergency.

A worry is that investigators have found more than half of those infected in the Chicago cluster had received some degree of vaccination.

Nallely Mora, research assistant professor at Loyola University Chicago’s Parkinson School of Health Sciences and Public Health, believes the cluster may be the result of people being negligent of getting a full schedule of vaccines.

She noted that while rates of mpox cases became extremely low, ranging from one to three confirmed cases per day in recent months, the virus never went away entirely.

“We know the rates of people willing to get a complete vaccine schedule is not great,” Mora said. “Some of them, they may have their first dose and then maybe they forget to get to the point of the 28 days, when they need to get the second dose to acquire full immunity, and it’s just not happening.”

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a health alert to U.S. doctors to watch for new cases. On Thursday, the agency published a modeling study that estimated the likelihood of mpox resurgence in 50 counties that have been the focus of a government campaign to control sexually transmitted diseases.

The study concluded that 10 of the counties had a 50% chance or higher of mpox outbreaks this year. The calculation was based largely on how many people were considered at high risk for infection and what fraction of them had some immunity through vaccination or previous infection.

At the top of the list are Jacksonville, Florida; Memphis, Tennessee; and Cincinnati — cities where 10% or fewer of the people at highest risk were estimated to have immunity. Another 25 counties have low or medium immunity levels that put then at a higher risk for outbreaks.

The study had a range of limitations, including that scientists don’t know how long immunity from vaccination or prior infections lasts. So why do the study? To warn people, said Dr. Chris Braden, who heads the CDC’s mpox response.

“This is something that is important for jurisdictions to promote prevention of mpox, and for the population to take note — and take care of themselves. That’s why we’re doing this,” he said.

Officials are trying to bring a sense of urgency to a health threat that was seen as a burgeoning crisis last summer but faded away by the end of the year.

Formerly known as monkeypox, mpox is caused by a virus in the same family as the one that causes smallpox. It is endemic in parts of Africa, where people have been infected through bites from rodents or small animals, but was not known to spread easily among people.

Cases began emerging in Europe and the U.S. about a year ago, mostly among men who have sex with men, and escalated in dozens of countries in June and July. The infections were rarely fatal, but many people suffered painful skin lesions for weeks.

Countries scrambled to find a vaccine or other countermeasures. In late July, the World Health Organization declared a health emergency. The U.S. followed with its own in early August.

But then cases began to fall, from an average of nearly 500 a day in August to fewer than 10 by late December. Experts attributed the decline to several factors, including government measures to overcome a vaccine shortage and efforts in the gay and bisexual community to spread warnings and limit sexual encounters.

The U.S. emergency ended in late January, and the WHO ended its declaration earlier this month.

Indeed, there is a lower sense of urgency about mpox than last year, said Dan Dimant, a spokesman for NYC Pride. The organization anticipates fewer messages about the threat at its events next month, though plans could change if the situation worsens.

There were long lines to get shots during the height of the crisis last year, but demand faded as cases declined. The government estimates that 1.7 million people — mostly men who have sex with men — are at high risk for mpox infection, but only about 400,000 have gotten the recommended two doses of the vaccine.

“We’re definitely not where we need to be,” Daskalakis said, during an interview last week at an STD conference in New Orleans. Some see possible storm clouds on the horizon.