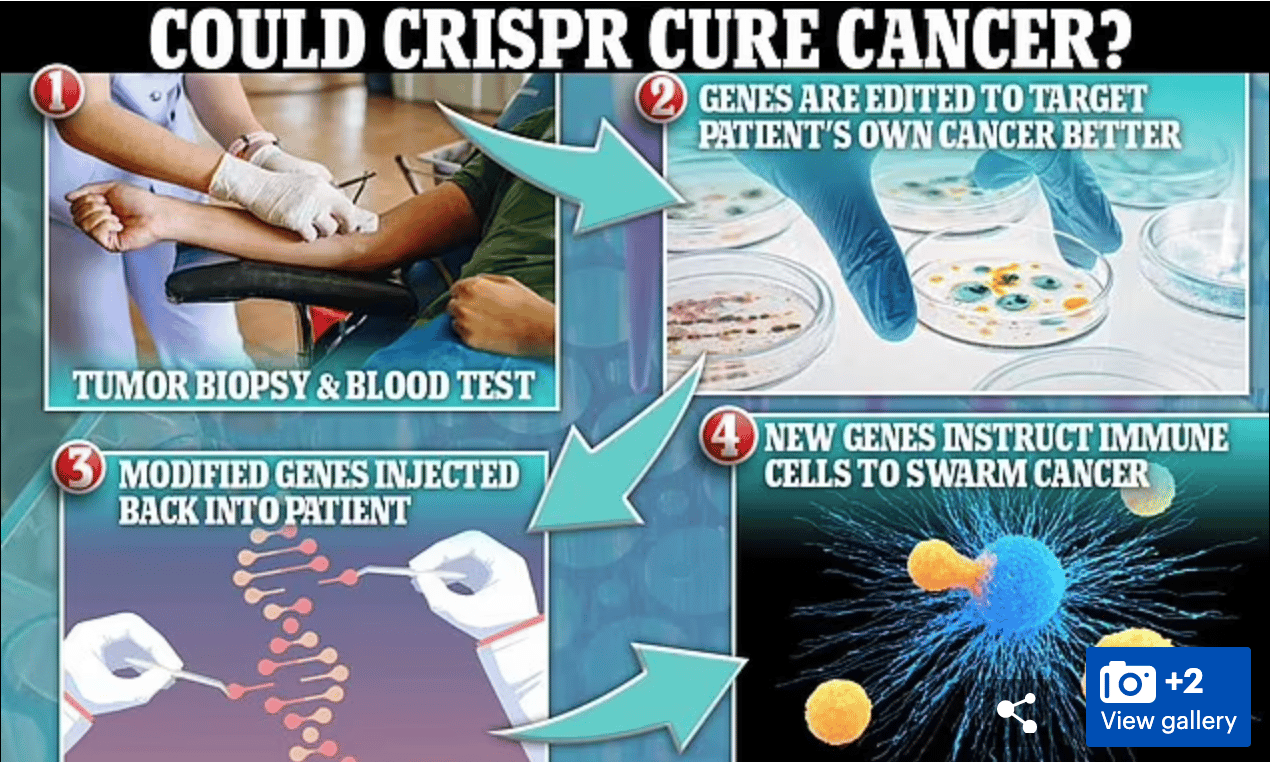

Scientists have tailored DNA-editing technology to turbocharge how the body fights cancer cells — in a potential breakthrough. They modified patients’ genes to instruct cancer-fighting cells to swarm tumors using CRISPR, which is given as a one-off injection. CRISPR has been previously used in humans to remove specific genes to allow the immune system to be more activated against cancer.

But the new study was able to not only take out specific genes, but insert new ones which program immune cells to fight the patient’s own specific cancer. Dr. Antoni Ribas, from the University of California, Los Angeles, and co-leader of the study said: ‘This is a leap forward in developing a personalized treatment for cancer.’

Researchers took blood and tumor samples from 16 patients with various forms of cancer including colon, breast, and lung. They isolated the immune cells that had hundreds of mutations targeted specifically at the cancers plaguing their bodies.

These were modified to be able to target each patient’s specific tumor, which have hundreds of unique mutations. One month after treatment, five of the participants experienced stable disease, meaning their tumors had not grown.

The CRISPR tool consists of two main actors: a guide RNA and a DNA-cutting enzyme. The guide RNA is a specific RNA sequence that recognizes the target piece of DNA to be edited and directs the enzyme, Cas9, to initiate the editing process.

Cas9 precisely cuts the target strands of DNA and removes a small piece, causing a gap in the DNA where a new piece of DNA can be added. Scientists design the guide RNA to mirror the DNA of the gene to be edited, known as the target. The guide RNA partners with the Cas9 enzyme and leads it to the target gene.

When the guide RNA matches up with the target gene’s DNA, Cas9 splices off the DNA, shutting the targeted gene off. Since the CRISPR technique has been around for about a decade and remains at the center of ambitious scientific projects.

Doctors are now exploring its application in treating rare diseases and genetic disorders such as sickle cell disease. ‘The generation of a personalized cell treatment for cancer would not have been feasible without the newly developed ability to use the CRISPR technique to replace the immune receptors in clinical-grade cell preparations in a single step,’ Dr. Ribas added. (SOURCE)