The two most successful coronavirus vaccines developed in the U.S. – the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines – are both mRNA vaccines. The idea of using genetic material to produce an immune response has opened up a world of research and potential medical uses far out of reach of traditional vaccines.

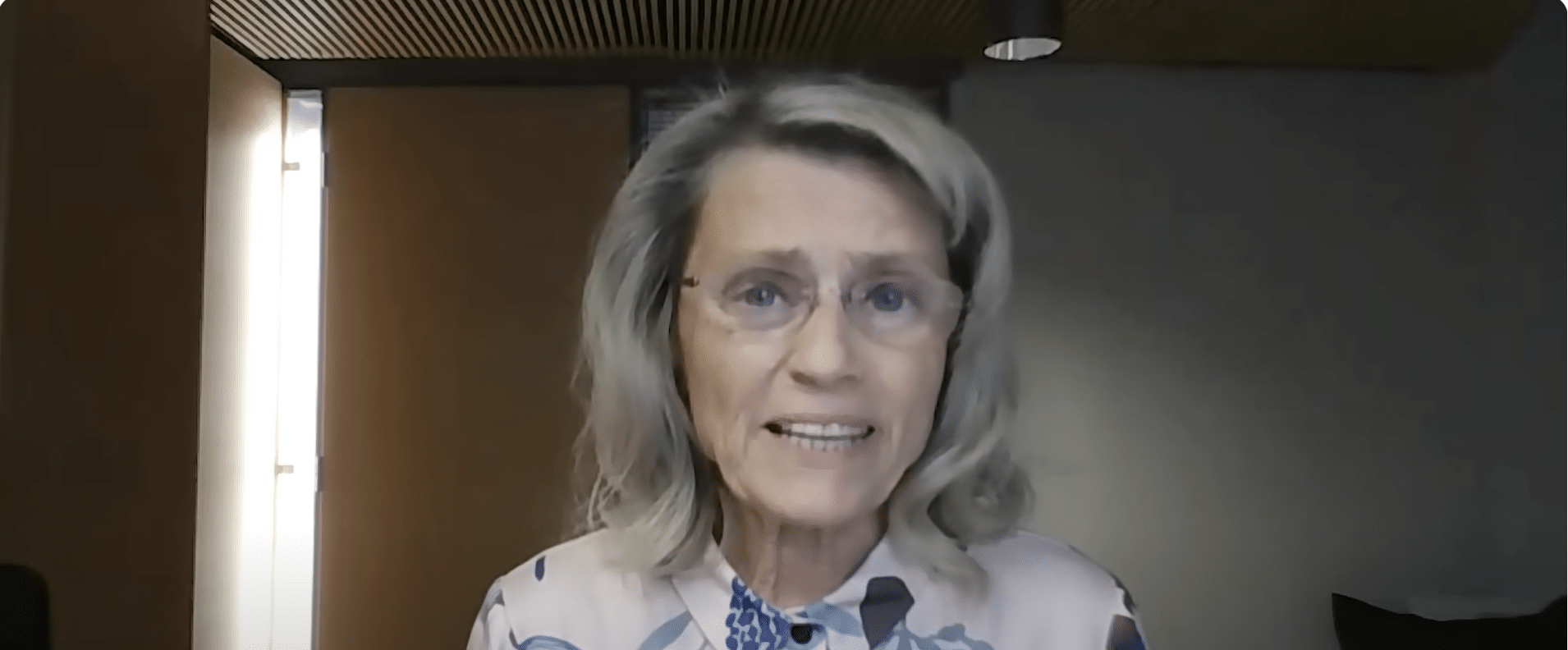

Deborah Fuller is a microbiologist at the University of Washington who has been studying genetic vaccines for more than 20 years. We spoke to her about the future of mRNA vaccines for The Conversation Weekly podcast. Below are excerpts from that conversation which have been edited for length and clarity. How long have gene-based vaccines been in development? This type of vaccine has been in the works for about 30 years.

Nucleic acid vaccines are based on the idea that DNA makes RNA and then RNA makes proteins. For any given protein, once we know the genetic sequence or code, we can design an mRNA or DNA molecule that prompts a person’s cells to start making it. When we first thought about this idea of putting a genetic code into somebody’s cells, we were studying both DNA and RNA.

The mRNA vaccines did not work very well at first. They were unstable and they caused pretty strong immune responses that were not necessarily desirable. For a very long time, DNA vaccines took the front seat, and the very first clinical trials were with a DNA vaccine.

About seven or eight years ago, mRNA vaccines started to take the lead. Researchers solved a lot of the problems – notably the instability – and discovered new technologies to deliver mRNA into cells and ways of modifying the coding sequence to make the vaccines a lot more safe to use in humans. Once those problems were solved, the technology was really poised to become a revolutionary tool for medicine.

This was just when COVID-19 hit. Most vaccines induce antibody responses. Antibodies are the primary immune mechanism that blocks infections. As we began to study nucleic acid vaccines, we discovered that because these vaccines are expressed within our cells, they were also very effective at inducing a T cell response.

This discovery really prompted additional thinking about how researchers could use nucleic acid vaccines not just for infectious diseases, but also for immunotherapy to treat cancers and chronic infectious diseases – like HIV, hepatitis B and herpes – as well as autoimmune disorders and even for gene therapy. READ MORE