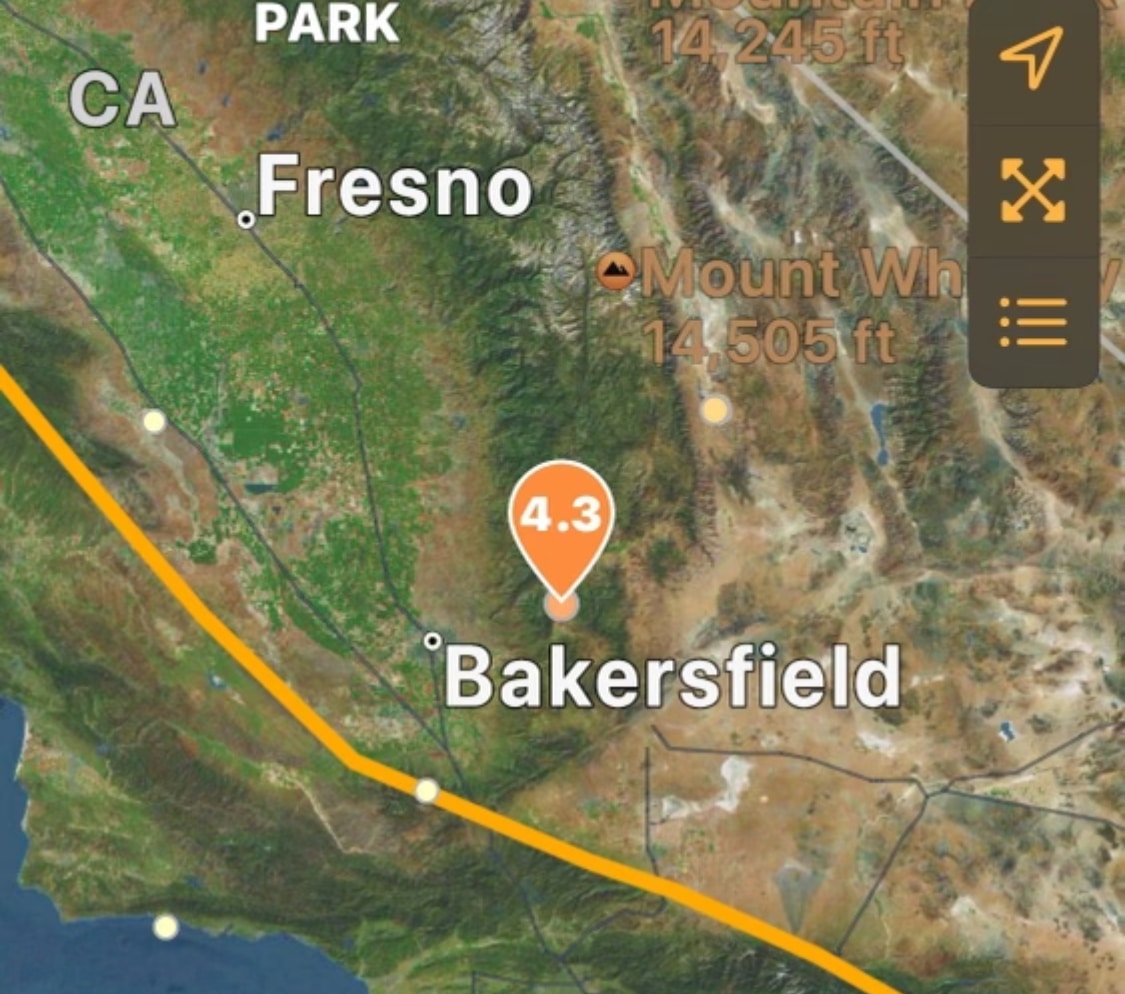

THE giant tectonic plates which make up Earth’s outermost layer are always on the move, sliding past and colliding with each other. This creates plenty of seismic activity, especially in the area around the Pacific Ocean known as the “Ring of Fire”, which accounts for some 90% of the world’s earthquakes. On April 14th a magnitude 6.2 tremor shook Kumamoto prefecture on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu. Then, in the early hours of the morning on April 16th, a magnitude 7.0 quake struck the same area. On the same day, on the opposite side of the ring, a coastal region of Manabí and Esmeraldas provinces in Ecuador was shaken violently by a magnitude 7.8 quake—15 times stronger in terms of the energy released than the second Japanese quake.

In Japan more than 40 people died; in Ecuador the death toll is expected to exceed 525. The greatest risk posed by earthquakes on land comes from buildings collapsing. Whether or not they fall down depends both on circumstance and on how they are built. This was evident in both disasters. In Ecuador, traditional homes made largely from bamboo withstood the quake better because of their flexibility. The more affluent, living in buildings made of concrete, were less lucky as walls, floors and roofs collapsed. FULL REPORT

I asked the LORD if the earthquake involving the New Madrid fault line would happen the day after Thanksgiving in 2005 because He has made me aware of its future danger.

His answer was like, “As it was in the days of Noah, so shall it be at the coming of the Son of man. They were eating and drinking and marrying and giving in marriage … And knoweth not that sudden destruction cometh upon them.”